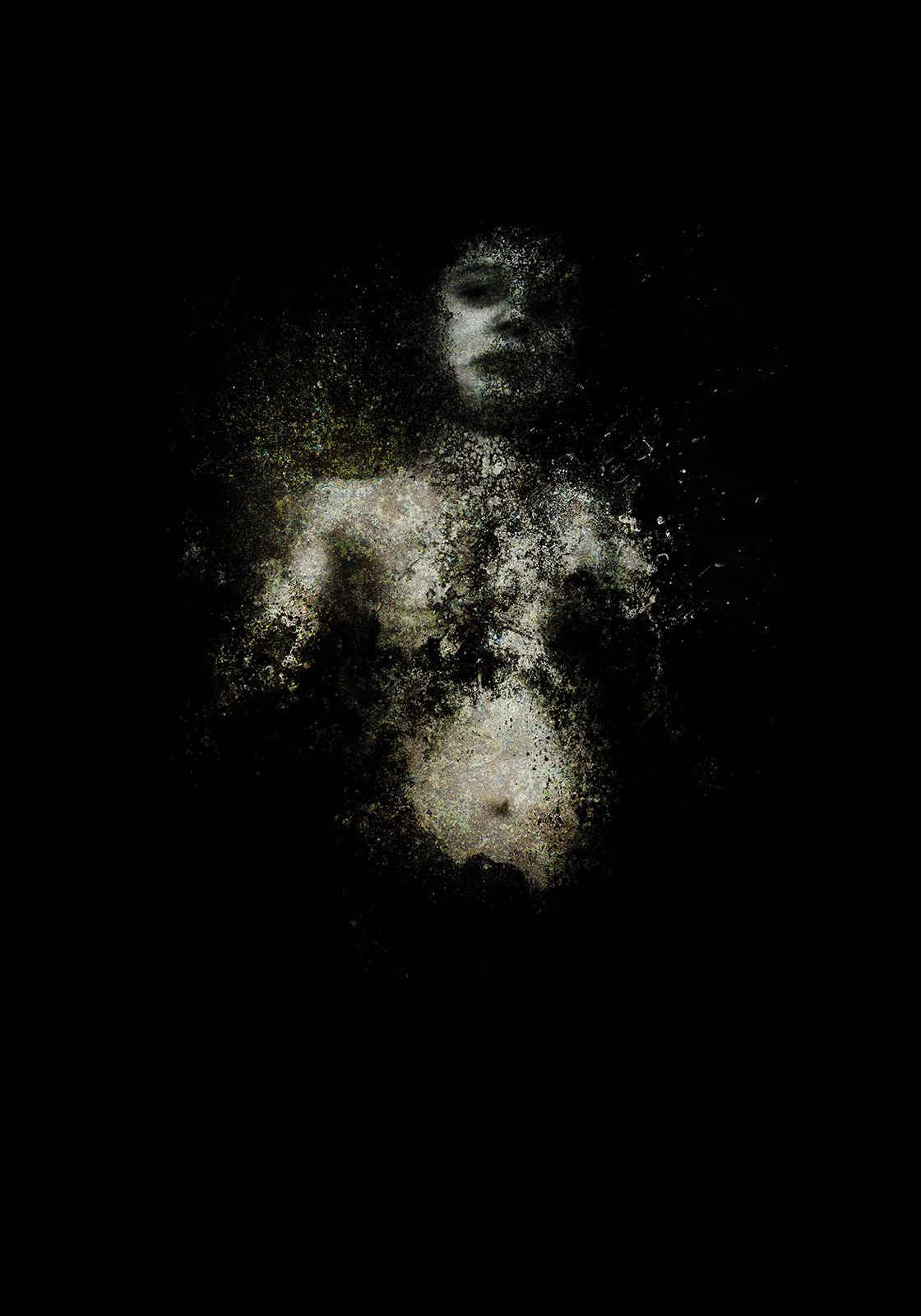

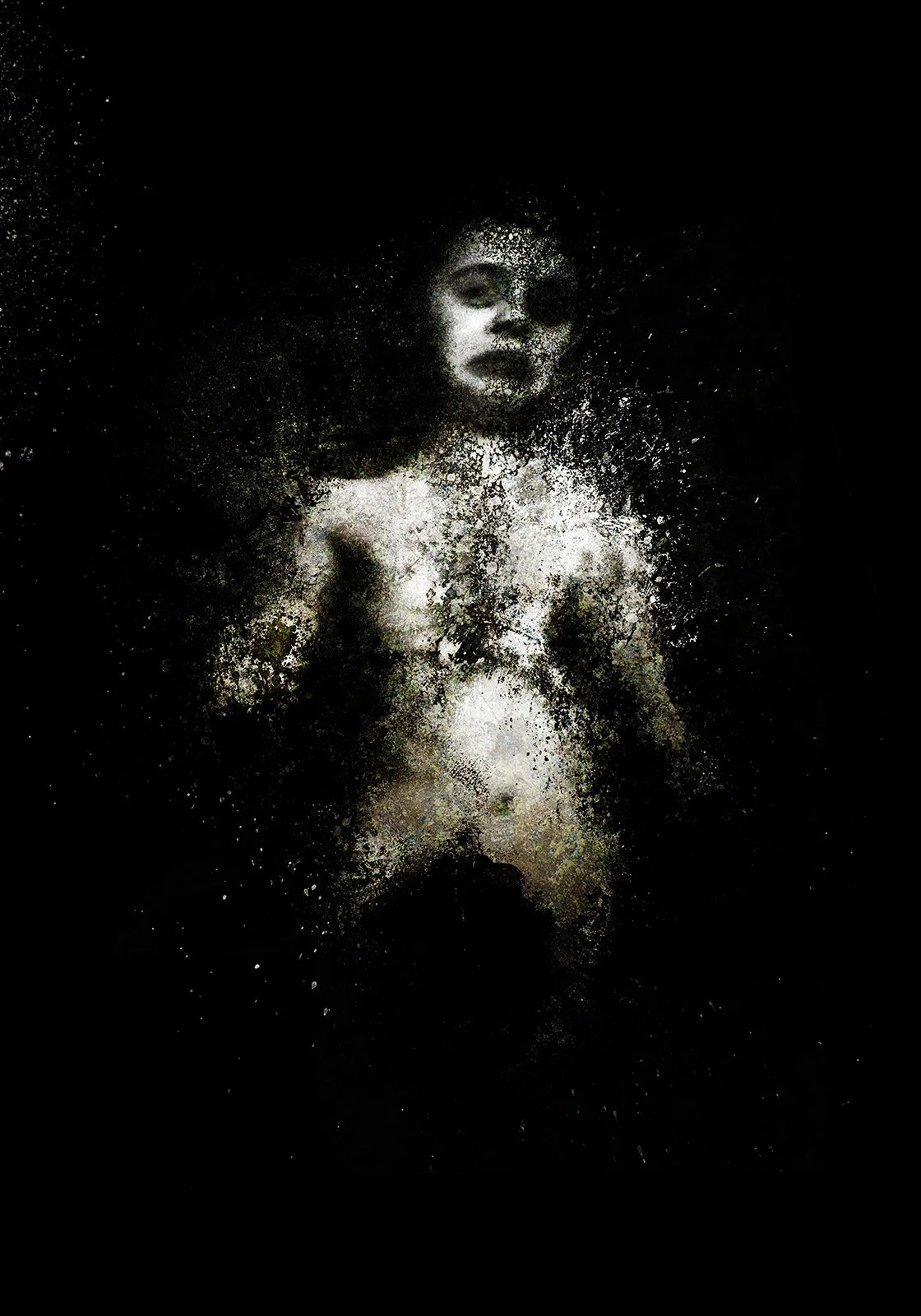

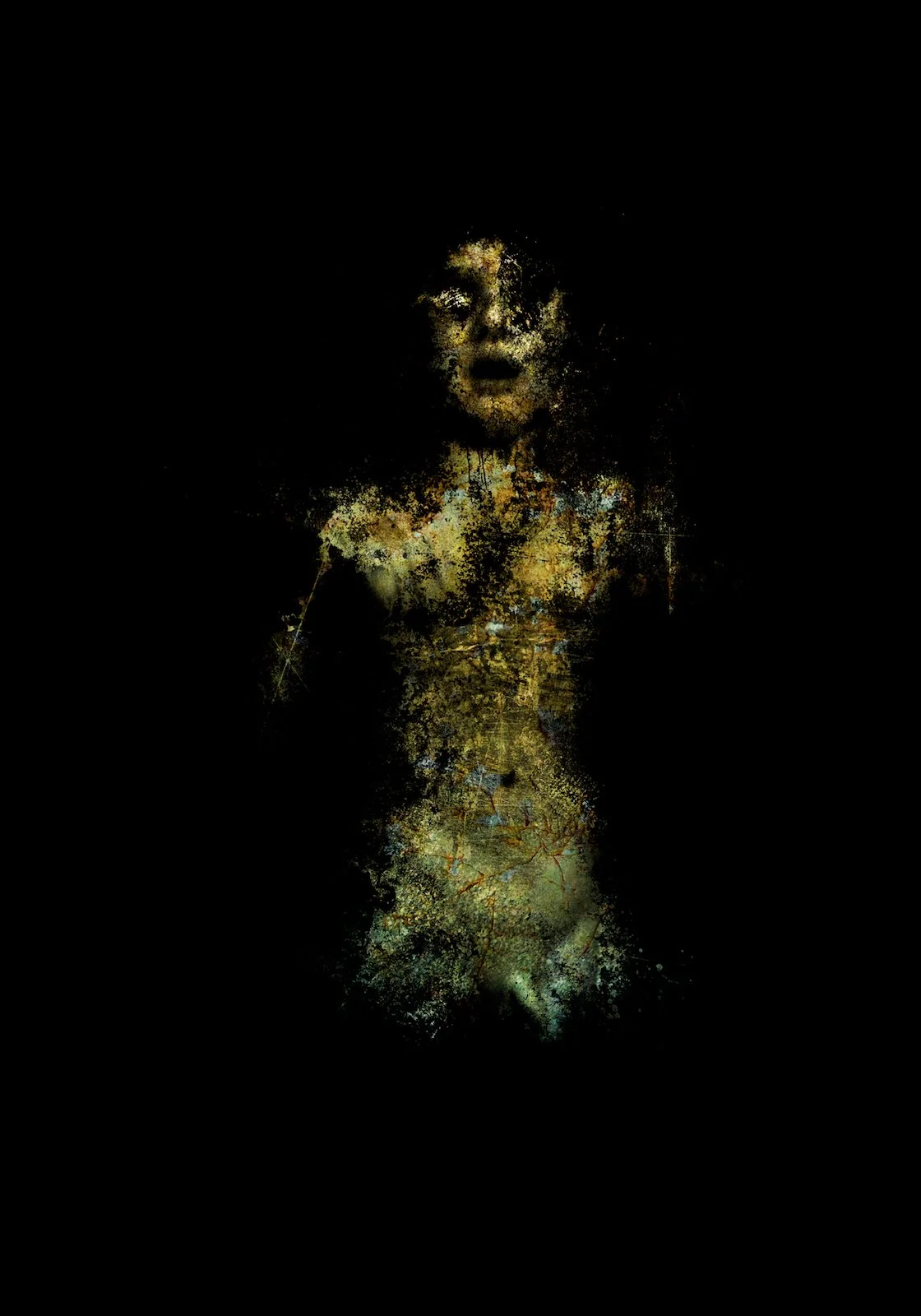

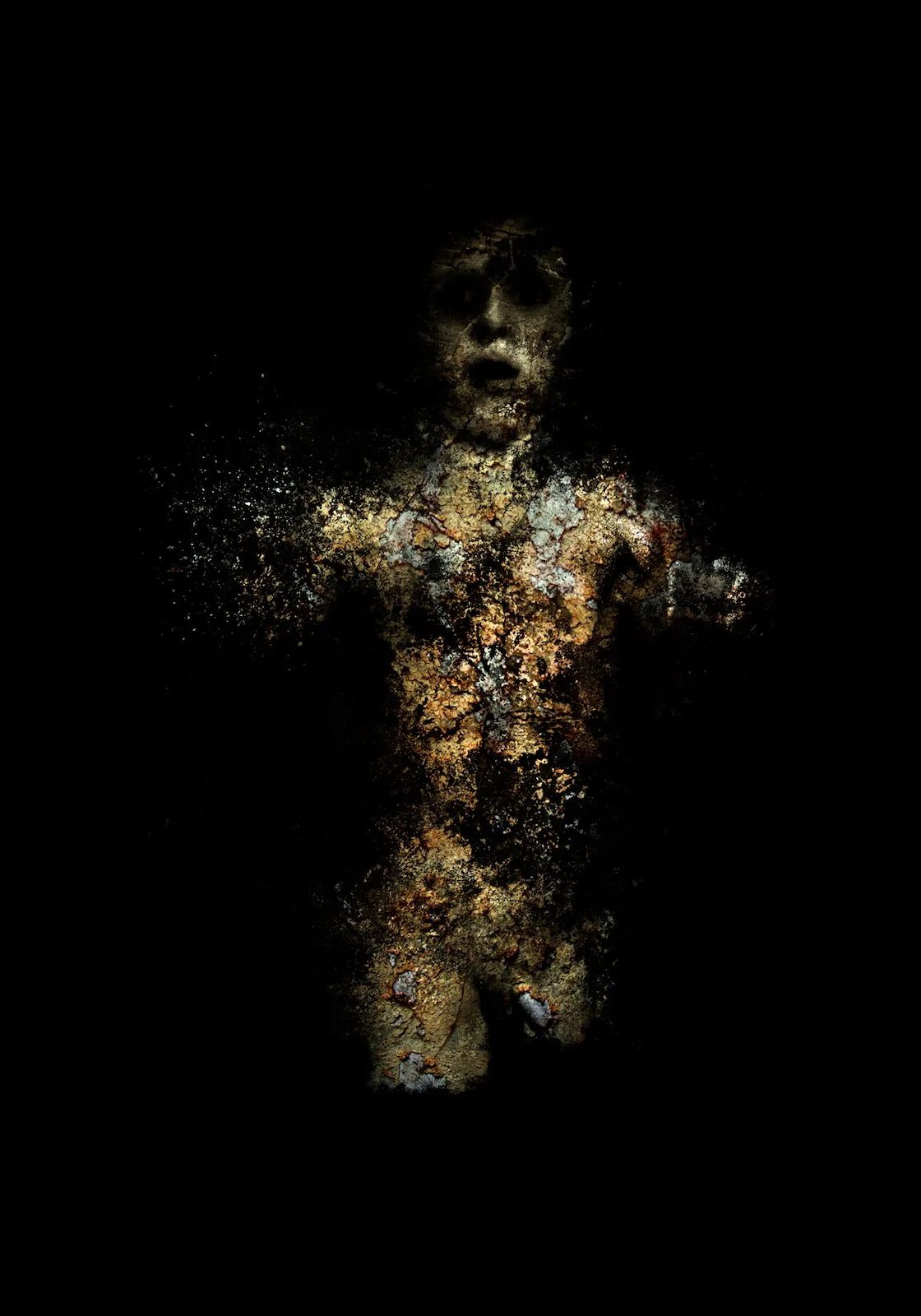

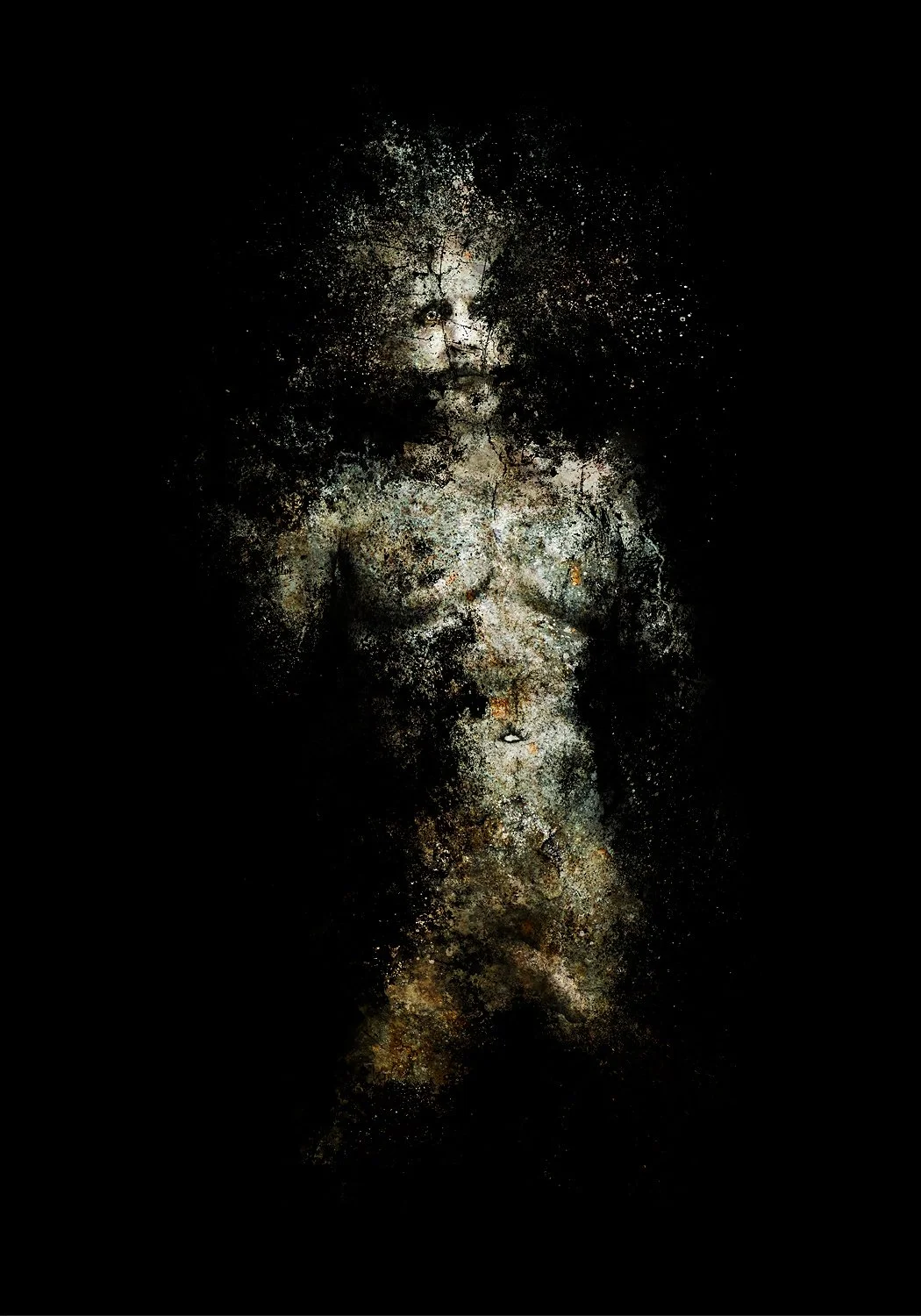

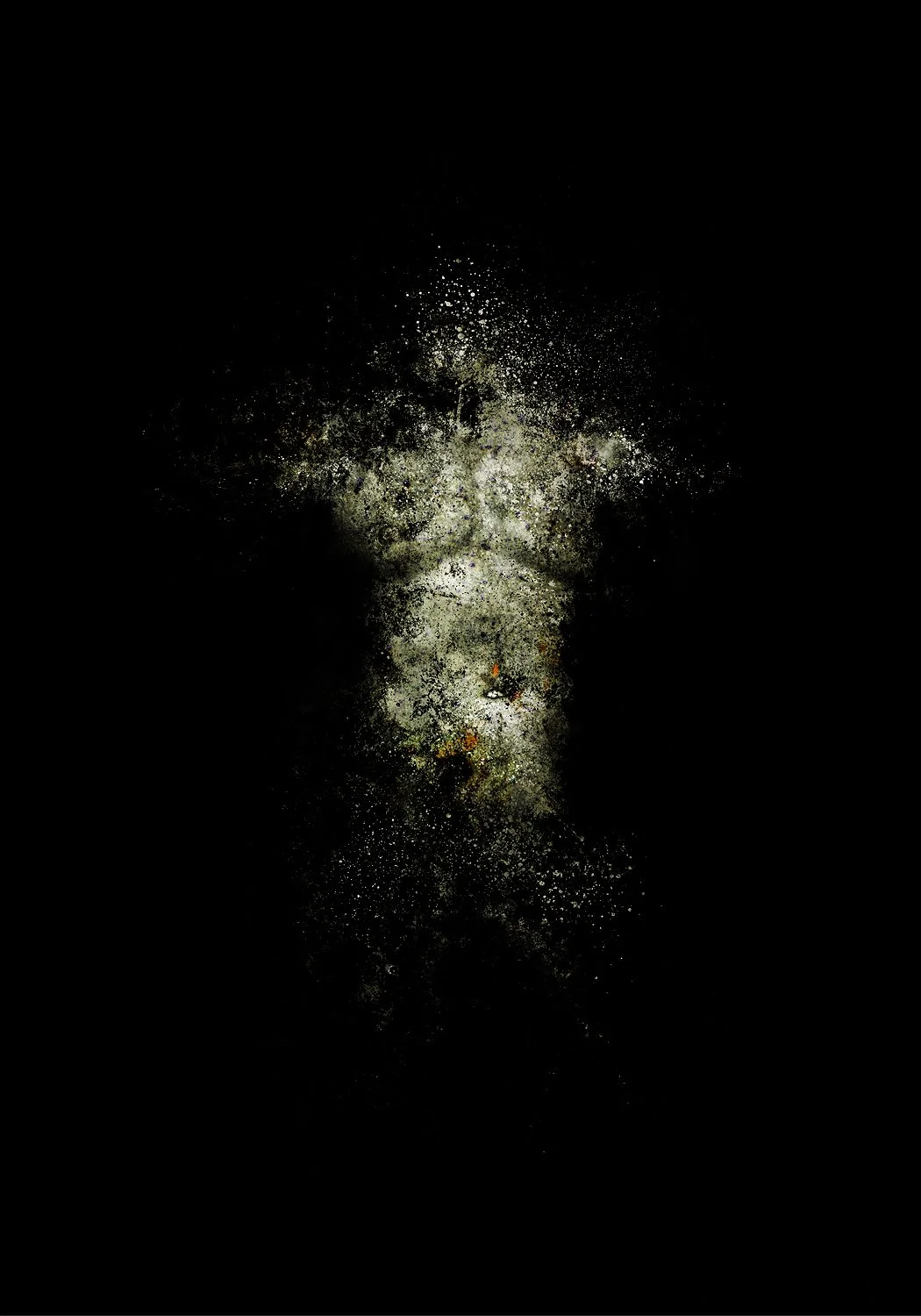

Everything Will Be Forgotten / Season of Mists

Frank Rodick, 2015

One way to say something about these pictures is to talk about the work I did earlier. Shortly after my mother died in 2010, I began work on a series of images, based on her life and death, that would become the Frances pictures. What happened, of course, was that these images said as much about me as they did about her. Which is always the way these things go. I settled on describing the Frances series (completed between 2011 and 2014) as a visual memoir of us both*—“of her, of me, of her and me stitched together in that sad and harrowing way we never stopped being.”

Till then I’d never made what I'd call a self-portrait. Maybe the pictures of my mother nudged me along. My father had died seven years earlier, so maybe it was the shadow of that last parent’s death—the rite of passage announcing that you’re now on the clock yourself. My mother's death signified different things for me. Mortality, of course, but more. A peculiar kind of loneliness that coexisted with the fact that more often than not her company was barely endurable. Freedom—from responsibility, from worry, from oversight. And an eerie sort of hope that came with an unfamiliar sense of clarity—a feeling that my life might now open onto a clearing—that I didn't know whether to trust or not.

I'd had years of practice roaming across time inside my mind. So I went back to the old albums, those heavy forest green binders with black pages. And the old shoeboxes, all light blue. There I found more old pictures, including small beaten up black-and-white snapshots of me as a child.

In those photos, I'm standing naked in a bathtub looking directly into the lens. My father is behind the camera. His handwriting is on the back of the prints, where he’s marked “1962.”

Looking at those photographs of that smooth-bellied three-year boy standing naked in a bath took some time to settle. I tried to remember what happened in those early days—things that happen in the secret lives of families, jagged and shabby. Those things, those events, resurfaced as occasional bursts of fire, but mostly as things that just, well, happened… over seconds, then minutes. Then years. But what seems more important, especially now, is that they, those things, never really left. They stayed… long shadows, sharp whispers, lead in the belly. Occasional but almost always silent cries from voices I can barely tell apart.

From that process came the images I called everything will be forgotten. And those images led to more reflection, this time on the present, on the man I’d become. As if created by a stranger, the images from everything will be forgotten gave me a shock with their peculiar violence. (This sense of unfamiliarity when I look at my own work, certain images in particular, never fails to startle.) But they also reminded me—like a crisp blow to the face—that no matter how I’d changed, roots are tough and deep enough to weather time. The pictures reminded me that to be human is to bear witness to fears and havoc, small and large, of long ago. That being human is to be a corporeal storehouse of a murmuring remembrance. That, until the end, the boy holds his ground inside the man.

I made more pictures right after that—the self-portraits titled season of mists, from the poem by Keats. They show me as I am now, a man with far more years behind him than in front. They show me living in the present, but, like us all, shouldering the past. And waiting for what comes next, as autumn waits for winter.