Frances

Frank Rodick, 2019

This statement was adapted from the longer essay “Stories of Love and Betrayal: On Making My Mother’s Portrait”

To read an essay on parade for the blind see “Blood Money and Reveries” published in Counter Arts.

To see the complete Frances series, click here.

These images are based on the life and death of my mother, Frances Rodick. Like almost all of us, she wasn't famous, or important in the sense of accomplishing grand and historic things. But she was—I admit this more than reluctantly—likely the most important person in my life. And, for better or worse, my instinct has always been to work from the place where my heart calls out the strongest. Or from where the most fear resides.

I’ve always said about these pictures that I began at the end. The very first image, called 97532, no. 1 (death), comes from a photograph I took of my mother two hours after she died in 2010.

97532, no. 1 (death)

© Frank Rodick, 2011

I didn’t start on a single one of these pictures until after she was dead. I briefly thought the timing was a coincidence, but that was a mistake, coming from a ridiculous bit of pride. I forget who it was that said artists should work as if their parents are dead, because a parent can be the most insidious censor, the kind that does its business from inside your mind and, even more treacherously, your belly. For these pictures anyway, there was no as if: I had to wait for fact and finality: her death. Hypotheticals would never have cut it.

I constructed most of these pictures from old photographs I found in family archives. Some were shot in 1942—the time when, unknown to Frances, that dark star in her life would begin to burn most fiercely an ocean away. My mother lived a long time, long enough to see empires rise and fall, long enough to see her family grow modestly, and then—through madness, disease, and rancour—wither. My mother lived long enough to lose a sharp and stormy mind—through mental illness, drug abuse, and, at the end, many years of Alzheimer's disease—piece by piece and, in the end, completely.

Frances Rodick was born to a life one degree of separation from a great catastrophe—the murderous disaster people named the Holocaust. She gave that horror a singular home inside her, and, through a process relentless and uncalculated, ensured it would be my home as well.

Both our lives showed me that Ibsen was right: sin and mayhem will run through generations, like blood through an artery. Quietly, sometimes. Critically, always.

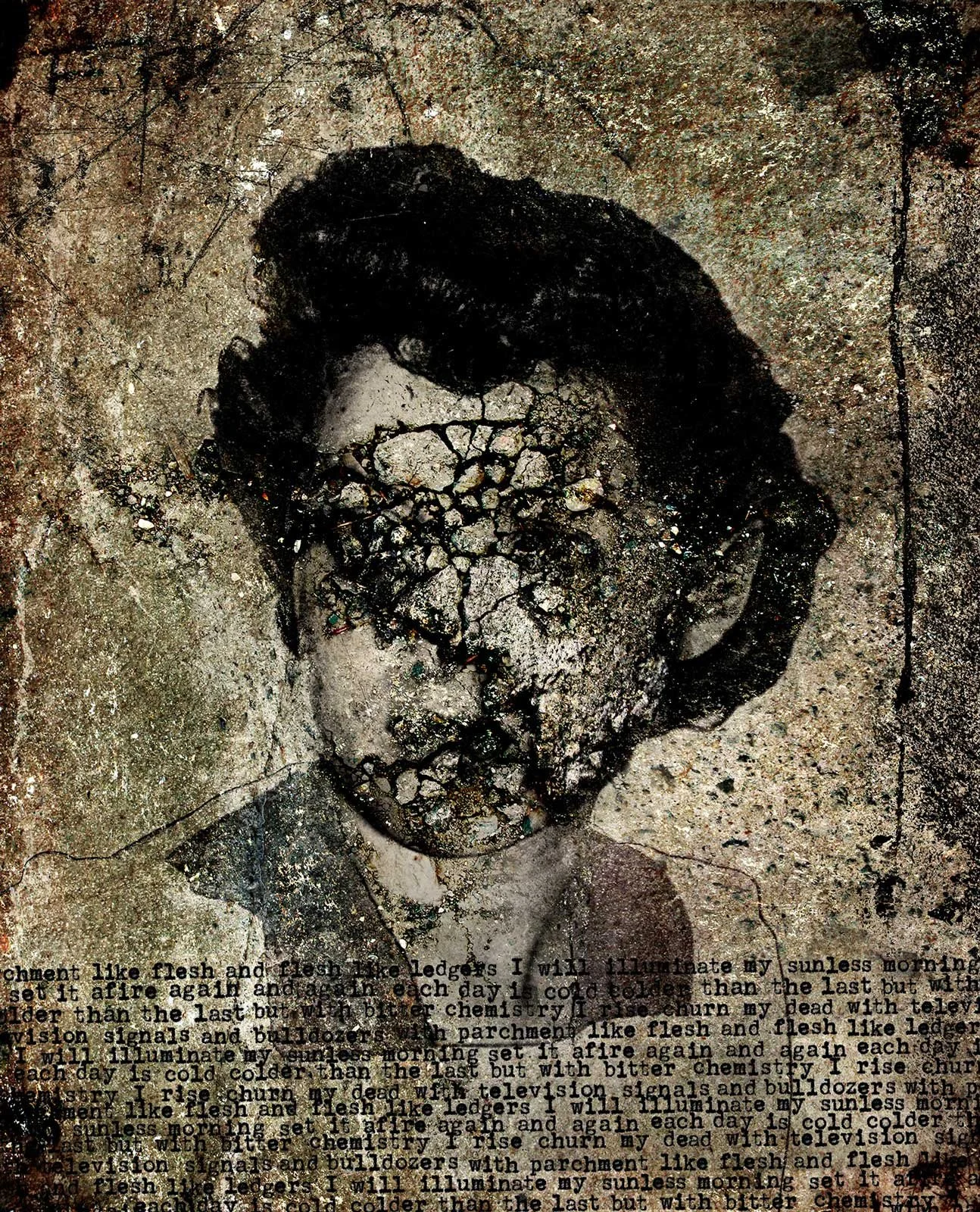

Frances (time)

© Frank Rodick, 2012

After my father's death in 2004, Frances endured nearly seven more years of what might carelessly be called life, existing as splintered body and razed mind. Watching those last years I saw the work of disintegration up close. The physical and the mental. What it does to the afflicted and to their witnesses. The way it makes seconds stretch into years and years compress into moments. The way it makes doing that one last thing impossible: words never said or taken back, that question never asked, a blessing wished for but never given, the questioning of what a blessing is worth in the face of an unravelling so invincible and indifferent.

There were things about my mother I admired. Her raw intelligence and sense of humour. The way she spurned God and Heaven, not just completely but fearlessly too.

But at her worst, which was far more often than anyone of us wished, Frances consorted with her torturing spirits. Together, they discharged a jagged pain into her shrunken world.

After her death, along with that large collection of family photographs, I studied my parents’ documents and papers. Some were old—birth certificates, business agreements, letters—and some more recent, mostly to do with the business of endings: wills, do-not-resuscitate orders, medical records, and, finally, death certificates.

Some of the text embedded in my images come from those papers. Other texts comes from historical documents such as the Nazi records that, in the timbre of an accountant, catalogue the wilful extinguishing of lives. Other words I wrote myself, searching—I realized later—for a voice that somehow would fuse my mother’s and mine.

An intersection of a single being, the thrust of history, and the memory of those still living: I suppose that’s one way of considering someone's life, and their death too.

Frances (each day is cold)

© Frank Rodick, 2012

The last image—the one I call parade for the blind—came from a photograph taken by my father. It was of a moment, a time, that should have been the best of her life. My parents were on vacation, something they never did when life got longer and darker. My mother was still young, physically healthy, married and without children, building a life of her own. But knowing her as I do, I think the devils and memories that plagued her were already at work.

I never had a plan in making these pictures. I never presumed to know where they would go. Most of the time it felt like they were leading me, pushing me this way and that, a couple of steps at a time over suspect ground.

Perhaps these pictures are a memoir—of her, of me, of her and me stitched together in that sad and harrowing way we never stopped being. If they are they're also hallucinations, because one hazards only a tremulous guess at knowing other people, including oneself and—especially—one’s parents. But if they are hallucinations, maybe they’re the kind Céline spoke of: constructions, some shining and some terrible, but in the end more real than the everyday experience of life. That's how it feels to me and, as I let it all wash over me, that that may even be where the remains of my hopes lie.

parade for the blind

© Frank Rodick, 2014