The Invisible Jury, on Wanting to See, and the Small Red Box: Notes on Making My Father’s Portrait

Frank Rodick, 2016

There’s music in everything, even defeat.

– Charles Bukowski

For a long time I didn’t think I’d ever make pictures of my father. He just didn’t mark my life the way my mother did. At least that’s what I thought. Also, I was angry. So maybe I was punishing him—posthumously even—by not making the effort. It’s common as dirt that people do such things. But I was angry with my mother too and that didn’t stop me from making pictures of her.

I’m not sure what happened to change things. Resignation maybe.

When it comes to things like remembering the name of a childhood friend, turning a stubborn key, or falling asleep, nothing helps more than giving up.

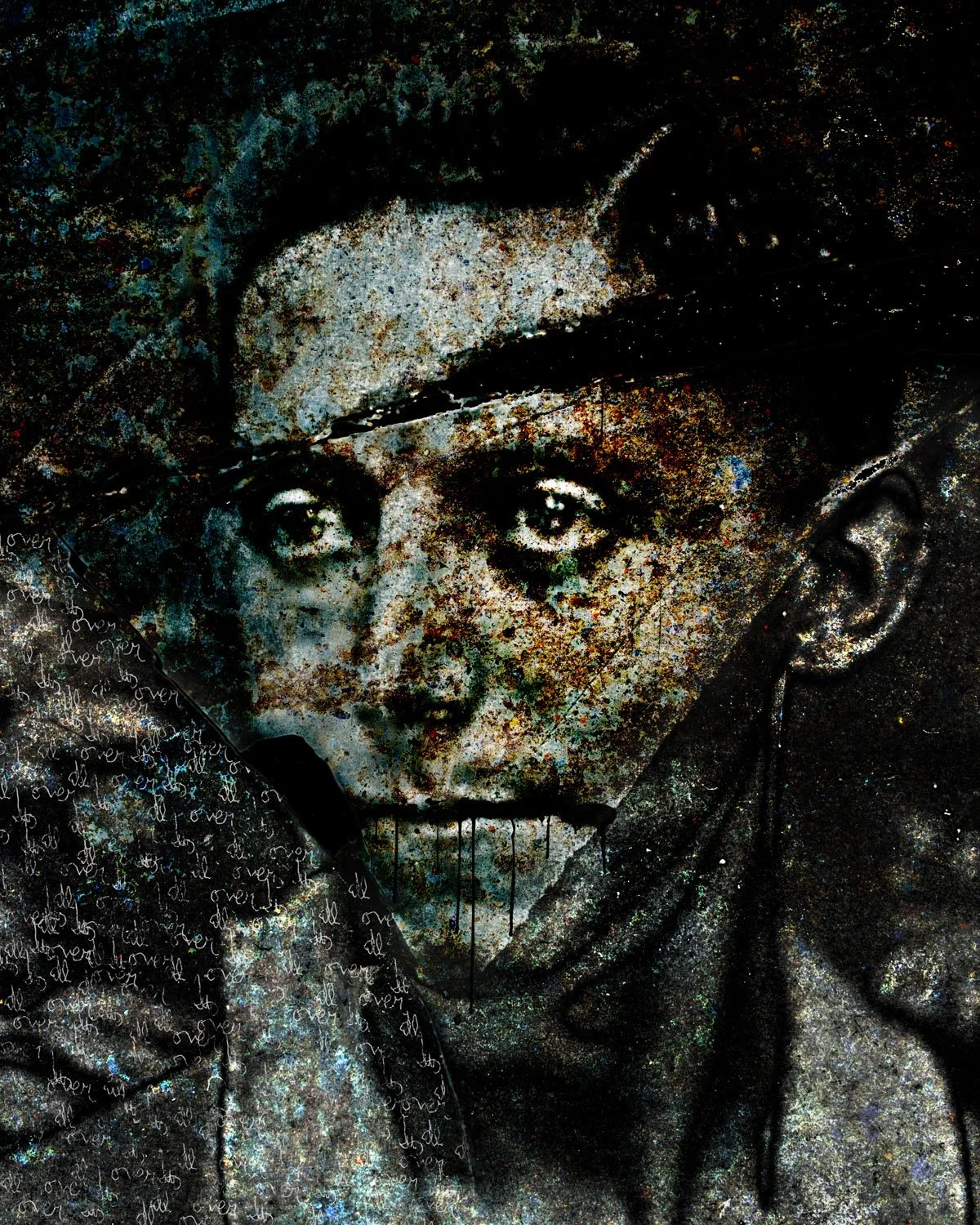

As with the pictures of my mother, I began the first of these images using old photographs I found in my parents’ stuff after they died. The original photos, small black and white prints, show my father at different ages. They start all the way back to a child of three standing next to a teddy bear. The teddy bear sits on a chair and he has this big button eye. Decades ago, I remember my father saying that this photo must have been taken in a studio because his home didn’t have teddy bears.

The text you see eked out in the first five images (and in the titles), are my father’s words during the last days of his life. Those days were predictably awful: hospitals, tubes and bedpans, mindfucking drugs—the indignities of a long life’s end, sadly commonplace. Intubated, he couldn’t speak. So, when he could, he wrote things down. Some stuff was illegible, some banal (I have a green notebook falling apart but still useful. I would like it here. Put a rubber band around it.), a few things cryptic. My father was proud of his beautiful handwriting, but by then those veiny hands shook so much all he could write were scrawls. I kept those pages and photographed them, so the words in the images (save for the last, which has none) are rendered directly from his own hand. His last words.

A difficult person to know, my father. (Yes, I know, so is everyone. But not equally so.) For one thing he didn’t trust anyone, not ever. I know he didn’t trust me because he told me so the one time I cornered him on it. That was just one more sad thing because, especially at the end, with my mother alive but demented, he had no one else.

Where did that mistrust come from? Maybe from a life through adulthood, full of hardship: poverty, war, sickness. Loss. An older sister who wrote her little brother Joe letters that my apparently unsentimental father kept always; she would die at 34 from tuberculosis. Then TB himself, a year in a sanitorium at age seventeen. No one visited me, not once, I overheard him telling someone, sixty years after.

Of course, the elder sibling of mistrust is fear. And my father feared. That austere early life didn’t help. His father supporting a family of five on the wages of a sailor and then as a driver for the rich. The Great Depression. Then the War, my father at home in England (no diseased lungs in the army, If I'd gone I’d have been killed right away, I know it, he told me once), alone with his mother who was literally shellshocked from the bombings. Weeping on the stairwell, I remember her, he said. And then later, a life begun with nothing alongside his bride Frances. I think he loved her—he photographed her constantly (okay, I see, I’m associating that with love)—but she was troubled to put it mildly, fighting and consorting with her own torments, more violent than his. When she’d explode and splinter, which was often, he’d take shelter, locking the door behind him and leaving anyone else (I’m talking mostly about myself here) to find cover on their own.

Sometimes, when I look at his eyes in these portraits I imagine them peeping through a cellar keyhole, checking to see if today’s hurricane has passed.

He wanted to be an artist, my father. He drew all the time, everywhere, and not badly for someone unschooled. The ritual I remember from childhood: flip over the paper placemat in Murray’s Restaurant in Montreal, and draw people with his ballpoint pen. But all that fear—especially poverty’s abyss, never far away—made a career as an artist more than just daunting. Instead he joined my mother and became a book seller. Life as a small merchant was hard but not ridiculous, not impossible like an artist's.

He also lacked those two essential qualities, underrated or even unnoticed by people who aren’t artists: a centered ruthlessness alongside relentless obsession. You need those if you want to make such a self-seeking and nebulous pursuit, with long odds against success (however defined), into your life’s mission.

When he saw me muddling my way into an art career—and it was he who introduced me to photography, let me give the man his due—my father was, on the surface anyway, pointedly indifferent at best. Actually, no; he hated it. In what felt like a taunt (and it was), all he’d ever say about my work was, How many pictures have you sold? (An effective barb—I sold little.) Other people said he was jealous—the schooled son who didn’t know poverty or war or sickness chasing the father’s dream. In any case, I responded to what I felt as meanness and rejection with the predictable: sullen expressions of meanness and rejection of my own.

Families.

Here’s a funny story. Some people chide me, saying it’s not funny at all. But, honestly, I think it is. My mother told the story, swearing it to be truth not mischief. The conversation:

MY MOTHER: On the day you were born do you know what your father did when the nurse told him you were a boy?

ME (wondering where this is going): I don’t know.

MY MOTHER: He fainted. Just like that, right then and there.

ME (incredulously, and realizing immediately that what I was about to say was ludicrous): You mean he fainted because he was overcome with emotion?

MY MOTHER (I imagine her suppressing neither laugh nor eye roll, and thinking her only child rather dimmer than she realized): No, because he wanted a girl.

ME: Wait, you mean he fainted from disappointment?

(At this point I’m thinking: Who in fuck faints from disappointment?)

MY MOTHER: That’s right.

Then we both laughed and, for a few minutes, liked each other in the way people do when they engage in minor familial conspiracy.

Apparently, months before my birth, my father, perhaps magically thinking it would tip the whole gender business his way, had chosen a name for what would be his only child. The baby girl would be Rita.

Rita Rodick, Rita Rodick. Try rolling that over your tongue a few times. Good grief.

Fast forward decades to September 2015 when I started this project, old photos of Joe Rodick scattered across my floor. As usual, I don’t know what to do with them, I dont’ know if there’s anything here at all. I don’t know what I want to say, or if I have anything to say. So I do as always: I wander in and out of the pictures, in and out of myself. Space and time, rinse and repeat. I get lost in the images and in all the ways they seem to become something else. Which is magical actually but it usually leads to me getting lost. I dislike feeling lost—which, unfortunately, I feel most of the time—and I get exasperated, fuck this and fuck that I say repeatedly, which I also do this often. I read and reread those seven chicken scratched pages of my father’s last words till my eyes bleed. Reading those pages over and over is weird—sometimes I find a whole sentence that I'd swear I never saw before.

I spend a good amount of time feeling sorry for myself, for a whole bunch of reasons. And, at times, when my father’s picture becomes more than just an image, I feel sorry for him too. More sorry than I ever did when he was alive.

I go up and down alleyways, most of them blind. Blind, but not mute—they all have something to say, even if it’s just a whispered nudge in one direction or other. I work and, even more important, I wait. (I hate waiting.) I wait for the pictures to tell me what to do next.

Joseph (2004/09/26/00/15)

That final image—Joseph (2004/09/26/00/15)—is the only one without those last words. I took the original picture myself, of my dead father. I wasn’t there for that moment, arriving about a half hour after, but when I got to the hospital, a nurse wearing glasses met me, escorting me to his curtained-off bed through a hallway silent because it was past midnight. What I remember most about her is that she was so solemn and it felt so sincere. I was shocked by that, and I still feel touched.

It’s funny, I’d brought a camera with me, so obviously I'd at least thought about taking some pictures. But it was this really crappy little thing, some prehistoric digital shitbox. It was as if, by bringing this inferior instrument, I was disclaiming, to that jury in my head, any inclination or instinct that might look predatorial. An alibi. No, your honour, I’m not the cold, callous snake of a son that I appear to be. If I were, I would have brought my large-format Bronica GS1. And my tripod.

Anyway, for ten or fifteen minutes maybe, I take photographs of my father. I remember the waxy skin, much yellower than I expected, another cliché that turned out to be true. But what I remember most was that dead mouth, gaping wide. It looked like he’d discharged those last wet shreds of life in a final breath. Or that they’d been sucked right out of him by some incubus who'd slipped back into that September night.

Joseph Rodick’s life ended in Montreal, at which hospital I can’t remember because, between him and my mother, there were so many. On September 26th, 2004, fifteen minutes after midnight. That moment is represented by crisp numbers on his death certificate, laid out neatly by the Province of Québec.

Joseph (I wanted to see)

Joseph (I wanted to see))

When I look at my six images, what do I see? I see the human face of time—the juxtapositions and compressions, that what looks and feels like a long life is a cipher. Emerging from a life left in more ways than one, I see what looks like a man’s destiny and feels like a tragedy, a three year old with a teddy bear waiting, waiting to be the dying man mutely saying (pleading?), I am not ready to go. I see a boy, a man, looking—I am too, aren't you?—for something. I wanted to see, he wrote, at the end. But what?

I see the loneliest man I’ve ever known. Who died alone. And yes, so do we all. But some of us more than others.

And—this seems inevitable—I see myself. A man deep into Keats’ season of mists. The soft-dying day… that time, that place, where the strange twins of memory and astonishment drive their stakes into heart and mind, claiming one more piece of territory.

A few months after my father died I was going through his things and found a small red cardboard box I'd never seen before. SIMPSONS it said in cursive gold lettering: the name of a Montreal department store, long shuttered. Opening it, I found a sheet of thick yellowed paper, carefully folded to form a square pocket about two inches wide. I unfolded it, and curled inside was a snippet of blonde hair, delicate and fresh, as if cut yesterday. It belonged to my father’s sister—dead for over 70 years. Written in my father’s hand—my father’s beautiful hand—were five words:

Hair – lock of Rita Rodick.